|

Ahl, David H. - S2 - 313th ASA Battalion |

If you tuned in here by mistake, here are a few other places to go.

When I went off to college at Cornell University in 1956, just three years after the end of the Korean War, it was more-or-less expected that one would serve in the military one way or another. ROTC seemed like the most painless choice at the time. Navy and Air Force ROTC required four years on active duty while Army ROTC required only two years, so most guys opted for the Army. We had four semesters of coursework at Cornell and a summer of basic training at Fort Bragg. I got a more-or-less automatic deferment to complete a masters degree in engineering at Cornell and an MBA at Carnegie-Mellon.

When I went off to college at Cornell University in 1956, just three years after the end of the Korean War, it was more-or-less expected that one would serve in the military one way or another. ROTC seemed like the most painless choice at the time. Navy and Air Force ROTC required four years on active duty while Army ROTC required only two years, so most guys opted for the Army. We had four semesters of coursework at Cornell and a summer of basic training at Fort Bragg. I got a more-or-less automatic deferment to complete a masters degree in engineering at Cornell and an MBA at Carnegie-Mellon.

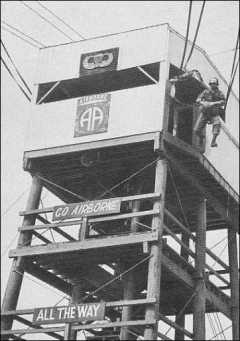

But then the inevitable day came, July 5, 1963, to report for active duty which commenced with three months of Infantry basic training at Ft. Benning. Do you know what the swamps of Georgia are like in July and August? That was followed by two months at Intelligence Staff officer School at Ft. Holabird, MD after which I reported to my duty station, the 313th ASA Battalion, a support unit for the XVIII Airborne Corps at Ft. Bragg, NC. The ASA is the electronic ears of the Army and they listen to enemy radio traffic to get an idea of the disposition and location of ground units before the main units are committed to battle. In fact, in a combat situation, units of the ASA would jump in with the pathfinders before the main drop, set up a listening post, and radio back intel so the commanders could better deploy the main Airborne units.

So with my background as a ham radio operator and degrees in electronics, one would expect that I would be assigned to the radio operations of the ASA. Except that we're dealing with the Army where logic doesn't play a role in duty assignments. In actual fact, I was made the Battalion S2 which in the ASA means security: security of the installation, of the equipment, of the code books, security clearances, and so on. I was also assigned such odd jobs as the assistant adjutant, test control officer, court martial appointing officer, re-enlistment officer, message classification officer (a huge pain in the butt), and, of course, officer of the day (OD) on a rotating schedule.

As OD in a STRAC unit (Strategic Army Corps), I had to make one formal inspection and one surprise inspection of the troops on night guard duty and (theoretically) stay awake all night cooped up in the commo shack. To make sure that happened, messages were sent from various headquarters to units such as ours with instructions to reply at 0330 or to call the duty officer in Company A at 0400. As a small unit with only 12 officers, OD rolled around far too often and although it was theoretically impossible, in my first year at Ft. Bragg, I pulled OD on Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Years Eve. The joys of being the junior 2nd Lt. in the unit.

As OD in a STRAC unit (Strategic Army Corps), I had to make one formal inspection and one surprise inspection of the troops on night guard duty and (theoretically) stay awake all night cooped up in the commo shack. To make sure that happened, messages were sent from various headquarters to units such as ours with instructions to reply at 0330 or to call the duty officer in Company A at 0400. As a small unit with only 12 officers, OD rolled around far too often and although it was theoretically impossible, in my first year at Ft. Bragg, I pulled OD on Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Years Eve. The joys of being the junior 2nd Lt. in the unit.

Also as the new kid on the block, I was asked (well, told) that since the unit did not have enough jump slots for everyone, I would not get one. Having a jump slot had pros and cons. Pros: an extra $110 per month and the thrill of jumping out of a perfectly good airplane. Cons: risking your life to jump out of a perfectly good airplane. After I saw my first death on Omaha drop zone (after two chutes streamered), I was more than happy to relinquish my jump slot for my full tour of duty.

The following June I was promoted to 1st Lt. and things improved somewhat. Nevertheless, apart from the semi-annual maneuvers (Desert Strike, Swift Strike) with the 82nd and 101st Airborne, and a couple of week-long training schools, the Army for me was basically one day of experience repeated 730 times. Dress up in starched fatigues and spit shined boots, report for duty at 0700, inspect everything that should be locked up, push around papers, another inspection, lunch mess, take care of ancillary duties, more paperwork, end-of-day inspection, hit the O-club, go home. Battalion briefing Monday morning, division intel briefing Wed. afternoon.

The closest I got to combat was when we loaded on the planes and flew to Homestead AFB in Florida during some flare up after the Cuban missile crisis. But it didn't amount to anything, the diplomats proclaimed that everything was now okay, and we flew back to Bragg.

I was married and we had a tiny house on the base, which was way better than the BOQ. Off duty I spent a great deal of time in the O Club drinking beer, in the wood shop (learned how to make furniture), hanging around Yarborough Ford in Fayetteville (remember Cale Yarborough, one of the top NASCAR drivers of the 60s and 70s?), and repairing my miserably unreliable Zundapp motorcycle.

Every time I asked for some leave, there was some reason that I couldn't get it. So when my two years were coming to a close, the CO said, "hey, you've got two months of accumulated leave, we can only pay you for two weeks, so you better take some leave before you get out." Thus it was that my wife and I took a space available flight to Europe, traveled around for six weeks, and came back to find myself transferred to an administrative out-processing unit. It seems that while I was gone, elements of the 313th was given orders to go to Vietnam and all the men were automatically extended for an additional nine months of active duty. But as they didn't know where I was (I had checked in once, as required, at Heidelberg), I was processed out and released from active duty on July 4, 1965. Just a few weeks later, the first elements of the 313th ASA Bn went to Vietnam with the 82nd Airborne.

Every time I asked for some leave, there was some reason that I couldn't get it. So when my two years were coming to a close, the CO said, "hey, you've got two months of accumulated leave, we can only pay you for two weeks, so you better take some leave before you get out." Thus it was that my wife and I took a space available flight to Europe, traveled around for six weeks, and came back to find myself transferred to an administrative out-processing unit. It seems that while I was gone, elements of the 313th was given orders to go to Vietnam and all the men were automatically extended for an additional nine months of active duty. But as they didn't know where I was (I had checked in once, as required, at Heidelberg), I was processed out and released from active duty on July 4, 1965. Just a few weeks later, the first elements of the 313th ASA Bn went to Vietnam with the 82nd Airborne.

I served out the rest of my time in the active and standby reserve, got my promotion to Captain on Sept. 21, 1967, and was released from the service on Feb. 23, 1968.

Today I am a member of the American Legion, American Airborne Ass'n, XVIII Airborne Corps Ass'n, War Cover Club, Universal Ship Cancellation Society, MVPA, and of course, the MTA. I mention the two philatelic organizations because after my hitch I started collecting first day covers and patriotic covers from WWII and now, with more than 5,000 covers including ones autographed by President Truman, Generals Eisenhower, MacArthur, Patton, Admiral Nimitz, Col. Doolittle, and others, it is one of the most comprehensive collections of its type in the world. I've exhibited some of these covers at APS, AFDCS, and USCS conventions and the exhibits have won seven bronze, silver, and gold medals over the years. I just recently sold 2,000 "extra" covers and I'm contemplating putting the primary collections on the market in the next couple of years.

Along with philatelic covers, I also collect model die cast military vehicles (and tow trucks) as well as full-size vehicles. I got my first military vehicle, an M37, in 1995, did a ground-up restoration on it, and sold it in 1999. I currently own a 1942 Chevy 1-1/2-ton tow truck (partially restored, but now for sale or trade), a 1971 M151A2 (running), and a 1987 HMMWV (combat ready).

D. Ahl Bio M37 Resto

© 2013. Web site design by Dave Ahl, e-mail swapmeetdave@aol.com